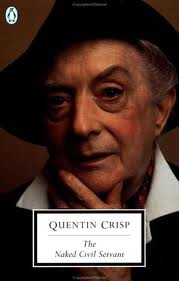

Book Review: The Naked Civil Servant by Quentin Crisp

My friend Marion recommended this book, with the polite but

unmistakable admonition to return it soon, and in good condition. When someone like Marion (a remarkable woman)

loves a book so much that she must have it by her side whether or not she’s

opened it in years, it gets my attention.

I read the book in a single day, the first time since I was

a teenager that I’d been so absorbed by a story I finished it within 8 hours.

I’d been meaning to read The Naked Civil Servant for

years. I had a vague idea who Quentin

Crisp was, but only that he was some sort of early 20th century gay

pioneer. In the 1990’s he made a series

of controversial statements about gay people, dismissing calls for equality and

insisting that homosexuality was an illness.

Like many others, I put these comments aside as the remarks

of an elderly man who didn’t understand the way new generations of gay people

looked at the world. Men like Crisp were

dinosaurs, the lumbering pioneers who had carried ideas forward but had collapsed

with exhaustion and were no longer useful.

I was right, but only partially. There was much more to the story than that.

Crisp was born in 1908, and while he covers his early years

with insight and wit (he declares that those who are thought witty are those

who laugh and listen politely to others – an insight I’ll have to test) the

story really takes flight when he moves to London .

By this time, Crisp has accepted that he is a homosexual and

has decided to confront the world with his existence instead of shading himself

in public, his head down. He slathers

his face with make-up, styles his hair in dramatic waves and wears flowing,

feminine fashions. He monitors every

step, one foot precisely in front of the other (I experimented with this gait

last night, and realized that it required a steady rocking of the hips).

Thus he sets out in 1930’s London , often drawing crowds of people who

follow him hurling insults, catcalls and rocks.

He is often attacked, and relates in a dispassionate voice the

techniques he used to get out of trouble, when possible. Of course, it was often not possible. Several times he is beaten, he often fears

for his life and danger is ever-present.

His presence inside large buildings would often cause a tumult and

shopping is an obstacle course of insults and rude clerks.

But still, he often finds work – in commercial art,

publishing houses and even an engineering firm.

This is no mean feat – his description of arriving for job interviews is

a delight to read, but I suspect it wasn’t nearly as amusing to live the

experience. Eventually he becomes a model for art students, a civil servant in his mind and thus the title.

Along comes World War II, and he is called in for his

physical. I laughed out loud several

times, the first being when a doctor told him with a hectoring voice meant to

induce shame that he exhibited all the signs of sexual perversion. Crisp happily agrees, telling him upfront

that he is a homosexual. This destroys

the doctor’s authority, and he huddles with others to discuss what to do. The whole scene is delivered with witheringly

precise descriptions of one absurdity after another.

His conflict with masculinity and femininity are interesting,

but maddening, delivered in a voice of authority that in the end he lacked. I’d have to read the book at a slower pace to

delve more deeply into what he meant by his somewhat contradictory approach to

gender roles. He idealizes the feminine

side of himself, and indeed with all homosexuals, but at the same time, he is

fervently in awe of masculinity, assigning it the treasured word of “normal”. And he is by turns dismissive and protective

of masculine gay men.

I admire his defiance of the world’s efforts to shame him, but

years of being followed by screaming mobs and inspiring chaos wherever he went

must have warped his mind. No human is

capable of withstanding that sort of abuse without acquiring scars, but Crisp

writes of his deepest disappointment with other gay people who criticized his

open defiance of convention.

Is this the root of his amorphous contempt for gay people

who seek equality ? For

all of his courage, at heart he accepted that he was a lower form of life than

straight people, so his defiance was based on acceptance of his status – the defiance

of the scullery maid who resents the intrusion of a parlor maid. He’d love that comparison, probably. Or hate it.

In the end, Crisp walked with his head up, but didn’t dare

look around, and while he was careful to place each foot just so, he was still

watching every step.

Comments

Post a Comment